Neurodiversity, Changelings, and what Fate: The Winx Saga can teach us about acceptance

As a transgender Latinx woman who is autistic and bipolar, I rarely see positive representations of neurodivergence on screen which I can relate to. So when I tried out Netflix’s recent show Fate: The Winx Saga, and saw a cast of relatable neurodivergent-coded characters with a plot based around the folklore of disability, I was immediately drawn into its world of faeries, magic, and mythology. The show has some problematic aspects including a lack of racial diversity, which illustrates the need for increased intersectionality in depictions of disability, and I hope to see a more diverse cast in future seasons. That said, the plot of season one ultimately shares a positive message of accepting and embracing neurodiversity, which is sorely needed on TV.

Fate: The Winx Saga, centers around a core group of five female teenage faeries attending Alfea College in the “Otherworld,” where they learn how to control their magical abilities. The way each character uniquely accesses magic through their thoughts and their emotions allows the show to metaphorically explore atypical neurologies and disability in nuanced ways, including main characters with autistic traits. The plot also revolves around the main character, Bloom, learning she is a “changeling,” a faery who was swapped at birth for a human child and raised by human parents. This myth, that of faeries kidnapping children and replacing them with changelings, has been utilized by many Western cultures for centuries to explain why certain children have developmental disabilities and neurodivergent conditions including autism.

Most traditional folklore on changelings is told from the parents’ perspective, and presents changeling children as dangerous, parasitic, and burdensome. This changeling folklore has been used to justify mistreatment, abuse, and murder of disabled children. Fate: The Winx Saga is unique because while it draws upon this folklore and shows Bloom’s mistreatment by others, including her parents, Bloom is the hero of the story. Instead of focusing on her parents, it instead focuses on Bloom’s journey to learn about her origins as a changeling, accept herself, and build healthy relationships with the other core group of faeries who help her accept herself.

All five of the main characters in Fate: The Winx Saga experience neurodivergence in some way, even if this neurodivergence is explained in-show explained as being derived from “faery magic” rather than human conditions like autism, anxiety, PTSD, and bipolar. Bloom has fire magic, Aisha, Bloom’s roommate, has the ability to control water, Musa is an empath, Stella can control light, and Terra can control earth/plants. All five of them have experienced some form of marginalization related to their powers. As Aisha (who once accidentally flooded her school’s toilets) jokingly tells Bloom, “being a faery, sometimes you have to deal with shit.” As each of their connections to magic is linked to their emotions, each faery’s journey to controlling their powers follows a unique path that involves them coming to terms with personal trauma and accepting themselves.

I saw aspects of my experiences with neurodivergence in almost all of their emotional journeys, and that’s very rare in a show for me. Bloom has a sense of righteous anger and difficulty trusting other people because of her history of isolation and abuse; Terra is the decidedly un-cool hippie girl who has to stand up to bullies and people trying to take advantage of her big heart; Aisha hides her social anxiety through focusing on athleticism and academic study; Stella has difficulty feeling agency over her own life because of her parents’ expectations of her; and Musa’s intense attunement to other people’s leads to sensory overload in prolonged social situations requiring her to frequently retreat into isolation.

When I posted these descriptions of the characters to an online support group for autistic women & nonbinary people to see if others related to my observations, I was met with many affirmative responses. It led to several new people exploring and becoming fans of the show, and existing fans sharing which character they related to the most. Musa was the character most referenced. Personally I initially related most strongly with Bloom, but Musa was a close second, and I’ll also examine both of them more in more depth.

My post on this autistic support group also led to some really important debates on certain problematic aspects of the show and how it left people feeling both excited but also disappointed. Many people critiqued the differences between Fate: the Winx Saga and the source material it was based on. Fate: The Winx Saga is based on an Italian cartoon called Winx Club heavily inspired by Magical Girl anime. I honestly had never seen Winx Club before I watched Fate: The Winx Saga, and while since then I’ve educated myself about Winx Club, I can’t say I’ve become a fan of the cartoon. Two main reason are that, to me, the cartoon doesn’t really seem to explore neurodiversity, and it also doesn’t reference the folklore of disability, with Bloom simply being adopted by human parents rather than being a changeling. Regardless though of one’s opinions about the merits of the two shows, there’s one inarguably major problem with Fate: The Winx Saga: Netflix’s TV show has a less racially diverse cast than Winx Club.

One of the key lessons of intersectionality is that one form of diversity should not come at the cost of another. Representations of neurodiversity, queerness, and body diversity in Fate: The Winx Saga do not in any way excuse the lack of racial diversity in the cast and characters. Aisha, who is Black, is the sole person of color in the main group of five faeries, and her story is less developed than other characters in the group, especially because she’s mainly portrayed as supporting Bloom in some way. None of the five main faeries in season one of Fate: The Winx Saga are Latinx, whereas Winx Club had a Latinx faery named Flora. As a Latinx women, I really feel that lack of representation.

One of the key lessons of intersectionality is that one form of diversity should not come at the cost of another. Representations of neurodiversity, queerness, and body diversity in Fate: The Winx Saga do not in any way excuse the lack of racial diversity in the cast and characters.

Kayley margarite whalen

Musa is perhaps the most troubling example, as her character in Winx Club was inspired by Chinese-American actress Lucy Liu, whereas Musa in Fate: The Winx Saga is white. They’re fundamentally different characters in many ways, with Winx Club’s Musa being very social and having powers linked to music rather than empathic abilities, but that’s no justification for Musa to now be white. It’s a huge shame that Netflix re-envisioned Musa as a relatable autistic-coded character while at the same time leaving out her Asian-American background. Personally, I feel an incredible sense of cognitive dissonance in how I feel betrayed by the whitewashing of Musa’s character by Netflix, while at the same time deeply appreciating how Musa in Fate: The Winx Saga feels like a really positive representation of an autistic woman. This cognitive dissonance is unfortunately far too common for neurodivergent women of color, and other multiply-marginalized disabled people. We get to see one aspect of ourselves represented, but in a narrow way that doesn’t acknowledge how the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality inform our experience with disability. So while I enjoyed Elisha Applebaum’s acting, and Applebaum’s personal background points to the fact that she likely is neurodivergent herself (such as her experiences with anxiety) I have no doubt that a neurodivergent API (Asian/Pacific Islander) actor could have also performed the role, which would have added additional depth and intersectionality to Musa.

So with this in mind, I first want to explore Fate: the Winx Saga’s Musa more in depth, as her neurodivergence seems the most obvious than the other characters.

Musa: autism, empathy, and sensory processing disorders

In Fate: The Winx Saga, Musa is a “mind fairy,” which gives her magical ability to sense other people’s emotions. This ability is shown as frequently being debilitating to her. She has difficulty in group social settings and emotionally charged situations, because the intensity of the emotions her mind senses can lead to her experiencing sensory overload. Musa also experiences difficulty accessing her own emotions, as they can similarly be overwhelmed by sensory overload. Finally, the fact that Musa can sense emotions which other people may be trying to hide from her, and even from themselves, also has very negative consequences in that it makes Musa’s interactions with them often feel deeply unsettling. Musa tries to cope with these challenges in various ways, often with limited success. She almost always has a pair of large noise-blocking headphones with her. She uses these to help block out some of the sensory input from other people, and to access her own emotions through the music she listens to. Musa frequently needs to retreat into solitude and to take breaks from interacting with and talking to others.

Musa’s struggles with her magic empathic abilities closely mirrors the actual experiences of many autistic people, as well as other neurodivergent people who experience sensory processing disorders and/or heightened senses of empathy. Even if in-show the explanation for Musa’s struggles is faery “mind magic” rather than a human condition like autism, it’s clear that Musa experiences this magic as a disability, and that she has an atypical neurology (even for faeries).

Musa’s relationship with other characters also adds depth to her experiences of disability and humanizes neurodivergence in compelling ways. Musa’s roommate Terra initially accuses Musa as being insensitive and self-centered because she won’t socialize with her and wears her noise-blocking headphones in the room. Musa’s empathy then backfires on her in a very typically autistic way when Musa senses and reacts not to the emotions that Terra is projecting outwards — feelings of anger to Musa – but to the deeper anxieties about social isolation which Terra feels within herself. As Terra begins to learn through her interactions with Musa, it’s not that Musa is selfish or can’t empathize with her, it’s that Musa is able to empathize with her and other people on such a deep level she has to limit when she can be fully vulnerable to that empathy.

Musa later develops a romantic bond with another reclusive character named Sam (who she later learns is Terra’s brother). A key part of what Musa cherishes about her relationship with Sam is that he understands her need for solitude and is able to help her cope with her issues with emotional and sensory overload. It’s a rare example of a romantic partner on TV who seems to unquestionably support their neurodivergent partner. A gender nonbinary autistic fan of Fate: The Winx Saga, Katherine M, described to me on Facebook how “when Musa tells Sam that his energy is “the absence of chaos” I cried. That’s what my partner is for me.”

Towards the end of the season, we also learn how Musa is deeply traumatized by her mother’s death, especially as she was empathically connected to her mother at the moment of her death. This trauma prevents Musa from providing emotional support to Sam when he’s wounded and on the verge of death. While Terra and her father try to heal Sam, Musa flees the room, wracked by guilt but paralyzed into inaction by her trauma. Terra chases after her, again accusing Musa of being selfish. But when Musa explains to Terra how the source of her paralyzing trauma, Terra realizes yet again she’s the one who lacked empathy, and is able to support Musa so they can together help Sam.

This whole exchange is again incredibly relatable to me as an autistic person who has often been mistreated for how I experience emotions and empathy in ways that are neurodivergent. I have often faced mistreatment for times when I became unable to “hold my emotions in check.” This includes being disciplined for having a meltdown and crying at work, and yet those tears were related to the fact that my career is in writing about and advocating for marginalized people, which can involve overwhelming feelings of empathy. I’ve also experienced mistreatment by parents, friends, and romantic partners who’ve felt I was un-empathetic when I didn’t immediately react with what they saw as the proper emotional response to a situation. Oftentimes this was because, like Musa, I was processing much more than what was on the surface in that situation. This mistreatment can compile to create a belief that one is “bad at empathy,” which can make neurodivergent people feel they deserve mistreatment from others. Each time Musa stands up to Terra’s mistreatment, and each time Sam (and eventually Terra) supports Musa, it sends a positive message that empathizing and dealing with emotions in different ways from neurotypical people is okay.

Bloom: fire, passion, anger, and parental acceptance

Portrayals of Bloom’s experience with neurodivergence and disability is related both to certain personality traits, as well as her experience of being a changeling. From the very first episode, you learn how Bloom has experienced trauma and isolation for being different from other people her whole life. Her parents try to force her to socialize and have interests like a “normal” person, instead of her intense interests in things like tinkering with antique lamps and comic book superheros (both of these interests feel very autistic in nature). Her parents also punish Bloom for wanting to spend time alone, and her mother even calls her a “weird loner.” This abuse leads Bloom to discover she has magic abilities to control fire through her emotions, as these abilities are triggered one night after abusive treatment from her mom causes Bloom to accidentally set fire to her house and burn her mother. Bloom subsequently hides her powers and retreats further into isolation and shame as a result of the incident, until the headmaster of Alfea College finds her, tells her she is actually a faery, and invites her to attend Alfea to learn to control her powers.

As I’ve mentioned previously, at Alfea Bloom finds out there are others with powers like her, and she moves into a dorm with the core group of four other faery teenage girls. Yet she still struggles with isolation and bullying even in Alfea, as changelings are stigmatized and even called “dangerous” by other faeries. Bloom also struggles with trusting others after finding out her human life was basically a lie, which is made worse by the fact that the faculty at Alfea seem to be hiding the truth about why she is a changeling from Bloom. Related to Bloom’s struggles with trust, she often tries to solve things and master her powers on her own rather than accepting help from friends including her four roommates, whom she often lashes out against.

Bloom’s difficulty with maintaining healthy relationships and pushing away people who care about her, her difficulty making and trusting friends, her intense esoteric interests, her difficulty with emotions including anger which seem to rapidly and unexpectedly fluctuate especially when triggered by trauma, all point to Bloom being neurodivergent. For example, autistic meltdowns can lead to people lashing out when triggered and overwhelmed. I’m not a psychologist and I don’t want to armchair-diagnose Bloom, but many her traits I relate to because of both my experiences with bipolar and autism. These traits also are similar to some traits associated with Borderline Personality Disorder.

Fire is an element strongly associated with passion, anger, emotional volatility, and danger to oneself and others. This is exemplified in the emotionally volatile character of Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender who has elemental control of fire. It’s also no coincidence that leading bipolar scholar Kay Redfield Jamison titled her book examining bipolar artists throughout history Touched With Fire. Being bipolar can both contribute to incredible achievements driven by passion, but also can cause harmful and even fatal feelings of worthlessness, guilt, suicidal ideation, and violent anger at oneself and others. Bloom’s fire magic is portrayed as being extraordinarily powerful for a faery, driven by her passion, yet also dangerous because of her anger.

It’s ultimately the persistence of the other four faeries at trying to help Bloom, even after she lashes out at them multiple times, which eventually help Bloom control her emotions and her fire magic. Aisha’s water magic, which can literally douse Bloom’s flames, is used metaphorically to illustrate this dynamic. Thanks to her friends, Bloom eventually gains much greater control over her fire magic and defeat an attack on the school by magical ghouls called “Burned Ones” in the finale.

Finally, one of the biggest reasons the show spoke to me and others I’ve spoken to is because it offered a positive message that there can be a road to healing damaged relationships between neurodivergent children and parents who mistreated them. As mentioned previously, almost all changeling myths involve mistreatment of changeling children by parents, and focus more on parents grieving for their “normal” child they vainly believe has been kidnapped by faeries, rather than accept the child they do have. Various “treatments” for forcing a changeling child to reveal their “true” nature (and to get rid of them) included hitting or whipping the changeling, drowning them, or putting them in an oven, over a fire, or in boiling water.

This belief in changelings may seem to be a relic of a distant past, but in fact it remained widespread through even the end of the 19th Century, especially in Ireland, Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, and in immigrants from those countries. Dozens of historic and legendary accounts surviving today, including one from 1924. In almost all of these accounts, the parents abuse, abandon, or murder their disabled children in mis-guided attempts to drive the “changeling” out and get faeries to return their “normal” child back to them. In Fate: The Winx Saga it’s not entirely clear if the human child Bloom was swapped with was still alive, but the show seems to suggest it was stillborn because of a heart defect. This allows the show to focus on Bloom, and her parents learning to accept her as their child.

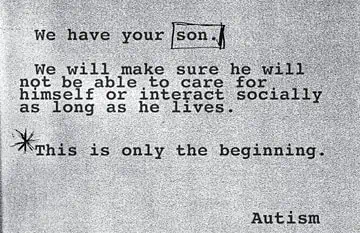

Even if few parents today literally believe in faery kidnappings, the concept that one’s “normal” child has been “kidnapped” by autism and other disabilities is incredibly widespread. These beliefs also are accompanied by other telltale signs from changeling mythology, such as how disabled children are portrayed as “burdens,” “dangerous” to themselves and other, and ultimately not being fully human. The language of kidnapping is used by many groups who advocate for abusive treatments for autism and dehumanizing notions that autism needs to be “cured.” This includes the founder of Autism Speaks, who explains how he was motivated to find a cure by his desire to “get his child back.” And the trope of children being “kidnapped” by neurodivergence was spectacularly put on display across the USA by an ad campaign which the New York University Child Study Center (NYU CSC) initiated in December 2007. This included billboards and magazine ads meant to look like “ransom notes” from conditions like autism, ADHD, and depression. These ads used stigmatizing, misleading language about these conditions to promote NYU CSC’s work to “cure” these conditions:

This so-called Ransom Notes campaign led to the growing Neurodiversity Movement organizing mass protests. The Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN) circulated a popular petition amongst grassroots neurodivergent advocates, and utilized this to publicly protest NYU CSC, eventually leading to them removing the ads.

The dehumanizing nature of children being described as “kidnapped” by neurodivergence, and the related idea that neurodivergent children are undue burdens has also led to many parents murdering their autistic children, often with few social of legal consequences. In some cases, the children are even blamed for “causing” their own murders. Every year on March 1, U.S. organizations aligned with the Neurodiversity Movement, including ASAN and the Autistic Women & Non-Binary Network host vigils known as the Disability Day of Mourning to honor the many disabled/neurodivergent people murdered by their parents, relatives, and caregivers today.. On March 1, 2021, these vigils, including a vigil organized by Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network and Autistic Self-Advocacy Atlanta honored 600 children murdered in the last five years.

Fate: The Winx Saga tells a very different story, that of Bloom’s parents learning to accept her. At the end of the first season when Bloom “comes out” as a faery changeling to her parents, they have to re-examine their past and learn to love who she really is. Bloom is able to have the strength to confront her parents because of her friends, who come with her. The scenes of her friends supporting her coming out, and then her parents crying together with Bloom while expressing their love of her literally made me cry. This depiction of Bloom trying to heal her relationship with her parents spoke to me as someone who’s struggled much of my life finding acceptance from my family for being both queer/transgender, and for being neurodivergent. I hope the show continue to explore this theme of parental acceptance, as in my experience, “coming out” and finding acceptance isn’t a one-time thing. Instead, it’s a gradual, non-linear process where initial acceptance may even backslide as parents or others struggle with changed relationship dynamics and what they see as a change in their reality.

Ultimately, I feel Fate: The Winx Saga is successful at portraying neurodiversity in relatable and nuanced ways. The fact that neurodivergent human conditions are never mentioned by name doesn’t bother me, because the show is set in a magical alternate reality with non-human characters. The way the show uses faery folklore and magic to portray common neurodivergent traits and feelings of marginalization may also help neurotypical fans of fantasy who might not be drawn to a show explicitly focused on disability to nevertheless gain an appreciation of neurodiversity. The way many fans “headcanon” characters like Musa and Bloom as autistic/neurodivergent is a positive sign that the show writers got something right.

Yet as mentioned previously, there is a major issue with lack of racial diversity in the show, and I hope Netflix listens to the show’s fans and critics and change this in season two. There are already precedents and signs that Netflix could add more racial diversity to the main group of five faeries. The original Winx Club cast had seven faeries by its conclusion, with Aisha added in season two to increase diversity. Flora is mentioned in Fate: The Winx Saga when Terra refers to her as her cousin, and many have seen this as a sign Flora might return. Netflix also did add a Black bisexual character to the cast of supporting characters known as “the Specialists,” martial artists who train in magical combat alongside the faeries. In Winx Club the Specialists were all white and heterosexual, and served mainly as the male love interests for the faeries. Dane is a character who breaks those molds. He struggles with bullying and accepting his sexuality, and develops a bond with Terra who defends him from bullying. Yet at the same time, Dane’s struggle with internalized biphobia also makes him vulnerable to being emotionally manipulated by other students (Riven and Beatrix) who don’t have his best interests at heart, which also sabotages his connection with Terra. Dane’s susceptibility to manipulation by others also feels authentic to the experience of many marginalized queer neurodivergent people, and I hope Fate: The Winx Saga develops that story further to show Dane realizing and breaking free from this manipulation.

I hope in Season two Fate: The Winx Saga focuses more on Aisha and Dane, as well as introducing more neurodivergent characters of color. This would also help the show gain a broader fanbase. There is a dearth of autistic and disabled people of color not only on film, but also in leadership roles in the disability movements. As a multiracial Latinx neurodivergent woman, I often feel a heavy burden to somehow “represent” autistic/disabled people of color. That said, I am proud to be on the board of directors of the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network and to be a communications consultant for organizations including the Autistic Women & Non-Binary Network and Sins Invalid, all of which I feel are making positive changes in building POC disabled/neurodivergent leadership. I just wish it didn’t feel so lonely and tokenizing at times, and I wish there were more role models for neurodivergent people of color to look up to, including nuanced fictional characters on TV. Netflix, can you please make that happen?

creator of TransWorldView blog

Fate: The Winx Saga