Autism in Latin American Communities

This post is adapted from a video by Kayley Whalen and is re-posted from her blog TransWorldView.

Hi, I’m Kayley Whalen, an autistic, transgender Puerto Rican and Guatemalan-American, and I’m here in Huehuetango, Guatemala to talk about autism in Latin American cultures. In this blog, I will be using the term “Latine autistics” to refer to autistic people in Latin America and of Latin American heritage.

Why I’m using the term Latine

So one note on language for this post is that I’m talking about Latin American cultures primarily in the United States, and there’s some debate around what term to use for people with Latin American heritage.

One of the older terms that I grew up with and many people still use is Hispanic, which is based on the language of Spanish and the origins of Spain as a country which was a colonizer of much of Latin America. Now, both because I’m not talking about Spanish-speaking populations, and specifically talking about populations from Latin America and in Latin America, the more appropriate term, which would also include Portuguese speakers, would be Latino.

Now, I also want to be inclusive of gender nonbinary people and gender neutral pronouns and language. So in 2014, the term Latinx became popular. However, more recently, especially native Spanish speakers and people in Latin American countries have started adopting Latine as a gender neutral term.

A few weeks ago, I actually recorded a video where I talked about my Puerto Rican and Guatemalan heritage, while referring to it as “Latinx” heritage. However, since then, the Autistic Women Nonbinary Network, whom I consult for, decided to switch to the use of “Latine” as it is easier to conjugate and the “e” ending matches better with traditional Spanish language vocabulary.

So I’m going to be talking about people of Latin American descent, and I’ll be primarily using Latine in this, although I may refer to myself as Latina as I do identify with a feminine gender identity and pronouns.

Latine Autistic people have always existed

Fact one about autism in Latin American communities is that autism has always existed in Latin American countries and in Latine populations in the United States. It’s just been under-diagnosed and misunderstood.

And I would say the science and medical literature has not really permeated much of Spanish speaking or Portuguese speaking Latin America in the way that it has English speaking populations in the United States. So when we talk about autism, we often think about how in the United States, there’s been a ton of visibility since the 1990s.

There was a surge in autistic self-advocacy in the early to mid 2000s in the United States. And I don’t think that surge has yet really reached many Spanish speaking Latine communities in the US, and that is part of what I’ll be discussing here about the need for more resources, information and advocacy for Latines, especially non English speaking Latine folks in the US and the need for kind of more international Latin American education and advocacy around autism.

So one thing I talked about in previous videos and blogs, and I’ll touch on more in this video is not only am I Latine, or a Latina, autistic person. My grandfather, Federico Saras, who I featured in a video where I talked about my Guatemalan and Puerto Rican heritage.

So Federico, Fred, my grandfather was almost certainly autistic, by every textbook kind of definition of it and all the facts that I’ve been able to glean from interviewing his friends, interviewing his doctor, interviewing his family. He certainly has almost all the markers of autistic behavior. And considering my whole life I’ve been compared to my grandfather, it is obvious to me, even if it’s not obvious to others that he had autism.

Also because most of the autism diagnosis criteria were developed in the 1940s; then unfortunately Bruno Bettelheim in the 1950s popularized some really awful ideas about autism. This was long after my grandfather would have been diagnosed or picked up, and we still have very low rates of diagnosis in Latin American communities, in adults, especially older adults. So he definitely was someone who was missed.

But to me and someone born around 1920, he’s proof that autism has always existed and it’s just been understood in different ways.

Why Latine Autistics are under-diagnosed

So fact number two is autism is under-diagnosed and diagnosed later in life for Latine children and adults.

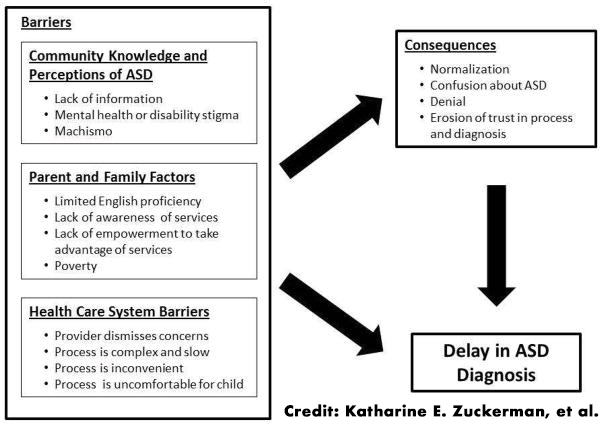

Now, one of the main studies that I’m going to cite is in Academic Pediatrics, and it interviewed 33 families, primarily Mexican American, about experiences around autism.

And in this study with interviews with parents, it identified many of the reasons that parents have difficulty getting diagnoses for their children and certain cultural barriers, which I’ll touch on later for why they might not seek out or understand an autism diagnosis.

Autism is diagnosed on average 2.5 years later in Latine children than non-Latine white children in the United States. And one of the big reasons for this is the lack of understanding and lack of materials, resources, and education for non-English speaking Latines.

So there’s a lack of articles in Spanish and Portuguese. There’s a lack of ability for English-speaking doctors to communicate to Spanish and Portuguese speaking Latine parents. Even those doctors who are Spanish or Portuguese-speaking may not have up-to-date information on autism.

One 2013 study looked in the California area at 267 primary care pediatricians to see how many autism offered screenings in Spanish. And of those 267 primary care pediatricians, 30.4% offered general developmental disability screenings for children and 40% offered Autism Spectrum Disorder screenings for children. But as for how many offer these screenings in Spanish, the numbers drop significantly. 17.7% offered general developmental disability screenings in Spanish, and 28% offered Autism screenings in Spanish.

So ultimately, of the 267 pediatricians, only about 1 in 10 pediatricians offered Autism screenings in Spanish. So this shows that doctors are less able to do diagnoses in Spanish. There’s a lot less doctors available.

Lack of research on BIPoC and Latine Autistics

One other thing which I’ll touch on autism for a lot of history has been seen as a white disorder; that the original studies done by Dr. Connor in the 1940s were done on white children, almost all of whom were in families that were in the upper middle class and socially visible. Many of them were in Who’s Who in America, and they were famous scientists. So children of scientists and well-to-do white families kind of set the example of autism as we’ve understood it for decades.

And unfortunately, this is still pervasive that there is a great lack of understanding of how autism manifests in non-white children and that as an aspect of racism, often autism is missed because there is often a perception that a white child might have a disorder and might need support. But a child of color who acts out can be seen as unruly, undisciplined, as a “behavior problem.” And they’re often diagnosed with other conditions that are somewhat have more stigma than autism.

Latine Autistics face systemic discrimination

Another fact to be aware of when talking about the Latine autistic population is the systemic discrimination, lack of access to health care, and lack of access to employment opportunities that Latine people face.

This may be related to immigration status or general racial bias and racial discrimination in society.

For Latina women in particular, they make extremely less amounts of money regardless of their educational status, immigration status, and job qualifications. They are making $0.57 for every dollar a white man would make for equivalent work.

In addition to this, Latines are amongst the least likely to have health insurance of different racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. So again, this lack of health insurance lead to a lack of support needs being met for autistic folks and lack of diagnoses. Anecdotally, the other Latin autistic folks that I know almost all received their diagnoses late in life, like in their twenties and thirties.

This includes my peer, Kayla Rodriguez at the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network and other peers, including Eric Michael Garcia, the author of We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation. I’m drawing some of the research for this post from his book.

So one other problem with getting a diagnosis for your autistic child is that often people of color, including Latine folks, often do not get taken as seriously or are told to “toughen up,” or that their symptoms aren’t real more so than white patients. And this is certainly true that some of the experiences in the Academic Pediatrics study that I looked at said that parents felt that “providers’ dismissive behaviors and or lack of inquiry into parents concerns delayed diagnosis.”

So again, this is not unique to Latine communities, but it is definitely a characteristic of marginalized communities where African-American/ Black communities are also often overlooked for symptoms that in a white person would be more commonly diagnosed. And that is true also, when we talk about Afro-Latines and Latine people who are Black and Brown.

Latine cultural bias against Autistic & Disabled people

There are certain cultural factors within Latin American cultures in the US and in Latin America, which lead to a lack of understanding, a lack of willingness to understand and accept autism, and a hesitancy or resistance to seeking out diagnosis.

So I want to approach this from a feminist and racial justice perspective that certain aspects of Latin American culture that we assume are part of the culture are aspects of racism and colonization.

And one of these cultural manifestations of racism and colonization that I want to talk about is Latino masculinity, often referred to with “machismo.” And for Latino men in the United States, machismo is very much tied to both the immigrant experience of needing to prove yourself that you’re manly, that you’re tough. And cultural biases and assumptions about Latino men, that they’re supposed to be tough, aggressive; gangsters; that they’re “spicy” inherently, that the aggressiveness is in their blood; these are very racist concepts and they’re harmful concepts for masculinity, that harm men and women, and they definitely harm autistic folks.

Here I want to talk about fathers. As the study I cited in Academic Pediatrics explored, many of the people who sought diagnoses for their children were the mothers. That when the mothers approached their husbands, that often the husbands were dismissive or they didn’t want to admit that their boy, or child, was somehow weak or disabled.

That in one case, where a mother who had been seeking a diagnosis for her child went to her husband, he said, oh, “nothing’s wrong with a child. You’re the one that’s crazy.”

And this, they explored further in this study with Mexican-American men who talked about how they wanted that tough kid that they could take with them to the rodeo, that they could show to their coworkers, and that their shame that reflects poorly on a man that they’re somehow weak or not macho or masculine enough if they have a “weak” child who is autistic or disabled.

So this shame about having a disabled child is not unique also to fathers, there are definitely accounts of mothers who kind of hide the fact that their child is disabled. One anecdote in this study talked about a family who would always close the door so their neighbors could never see that their child use a wheelchair.

Latine gender stereotypes harm Latine Autistic Women, Femmes, & LGBTQIA+ people

So another fact is that Latine autistic people are particularly harmed by race and gender stereotypes bias against Latine people. So this goes hand in hand with Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, which was formulated around being a Black woman. Latina women and femmes face particular discrimination in society that is unique to their identity.

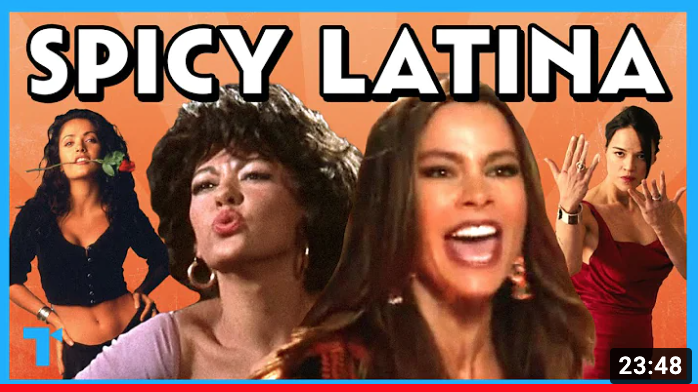

And I spoke with Kayla Rodriguez and helped edit a blog post that she just published on the Autistic Women and Nonbinary Network website. And in it she talks about the spicy Latina trope, which is a very common Hollywood and even pre-Hollywood trope from opera of the “spicy señoritas and hot tamales.”

The “Spicy Latina” is seen as sexually aggressive, unstable, “gonna steal your man,” very gregarious, loves to dance, loves to party; that type of woman.

Unfortunately for a lot of people, Hollywood and pop culture defines us. And for autistic people who may pick up on behavior and kind of mask by copying behaviors they might see on TV and media kind of copying the Spicy Latina trope is harmful.

I like to usually point to Mimi from Rent as the stereotypical “Spicy Latina.”

A lot of people talk about J Lo. Then there’s Carmen from the original opera Carmen.

These spicy Latinas; their sexual aggressivity and their flirtatiousness, is not always the healthiest thing for a young person to copy and think of as normal. It leads to poor body image. Eating disorders are particularly prevalent in the autistic community and among women and femmes, especially.

And it leads to this idea that Latine women are sexually available. 77% of Latinas, according to a study, have been harassed in the workplace.

For Latine women and femmes in the autistic community; who feel they can never live up to these stereotypes (and remember that it’s really not based on reality; it’s based on Hollywood and theater) there’s often a feeling that you fail as a Latina. I can very much relate to this that I’m not the gregarious dance-y, you know, super hyper-aggressive-type Latina who’s gonna steal your man.

And also I specifically say “man” because a lot of this trope is based around patriarchy and heteronormativity and that Latina women are expected to particularly be desirable to men and desire men.

So this presents a whole host of problems for the large number of LGBTQIA+ autistic folks, many of whom are Latina.

Beyond just Latine women and femmes and the problems they face with media representation, I don’t know of any mainstream media representation of autistic Latines. I’d love to see media representation of autistic Latines.

One more thing about gender stereotypes is, earlier, I talked about Latin American machismo in Latin American men. There’s often this expectation of being hypermasculine. Young autistic boys who are introverted, shy, emotional, prone to shutdown or meltdown; they are going to get bullied and mistreated for not living up to Latino machismo and patriarchal masculine stereotypes.

So stereotypes harm Latines both ways and can be particularly difficult for autistics.

And just one more thing is that we know that autistic folks are six to seven times more likely to be transgender or gender nonbinary. So these gender stereotypes really hurt all of the autistic community.

Police & carceral violence against Latine Autistics

One other fact to be aware of is that Latine autistic people are at a much higher risk of racial profiling, racialized violence, including police violence, incarceration, and violence in carceral systems, including institutions, than non Latine non-autistic people.

And of course, the combination with intersectionality, which we often refer to as “racialized autism,” that certain behaviors or characteristics of autism like stimming or repetitive behaviors or communication differences might be seen as threatening in a BIPoC autistic person that might not be seen as threatening in a white autistic person.

Now, one of the most extreme and disturbing examples of this was the shooting of Charles Kinsey, who was attending to a Latine autistic man, Arnold Rios-Soto. Charles Kinsey was a Black mental health provider/supporter for Arnold Rios-Soto, and police responded to a call that there was a man who was threatening to neighbors. They thought he might have a gun or be threatening suicide.

And in fact, it was the 27 year old Latino man, Arnold Rios-Soto, who was simply sitting outside of their group home (I’m not a big fan of group homes, by the way).

But Arnoldo Rios-Soto was sitting outside their group home playing with a toy truck, and the police thought it might be a weapon. Specifically, they claimed they thought it was a gun. And so Charles Kinsey, a Black man and a Latine man, were on the sidewalk, Charles Kinsey with his hands up in the air, trying to calm down Arnoldo Rios-Soto while trying to reassure officers that neither of them had a weapon, that they were not a threat.

And police officers later claimed they shot at Arnoldo Rios-Soto when they wounded Charles Kinsey in the leg. Then Arnoldo Rios-Soto panicked. He was detained. He was having an autistic meltdown understandably from someone being shot next to him, and they tranquilized him.

And it was very brutal police mistreatment of a Black person helping an autistic Latine person.

And this points to the fact that autism is often racialized as seen as a threat. I don’t believe that if Arnoldo had been white, he would have been seen as much of a threat with a toy truck.

Another example to talk about carceral systems and institutionalization is the Judge Rotenberg Center, which is infamous for using shock treatment, “aversive therapy,” on the disabled and autistic people there. Now, I don’t know the exact number of Latine people who are housed there, but we do know that the majority of people housed there are Black and Brown autistics.

So this is why I feel as an autistic movement, as a Latine movement, we really have to be working side by side with Black Lives Matter and attempts to defund, the police, and end institutionalization and carceral systems of all forms, in line with Disability Justice principles.

We need Latine Autistic Advocates in nonprofit leadership roles

Another fact is that Latines are very underrepresented in the disability and autistic movements, particularly looking at nonprofit organizations by and for disabled and autistic folks.

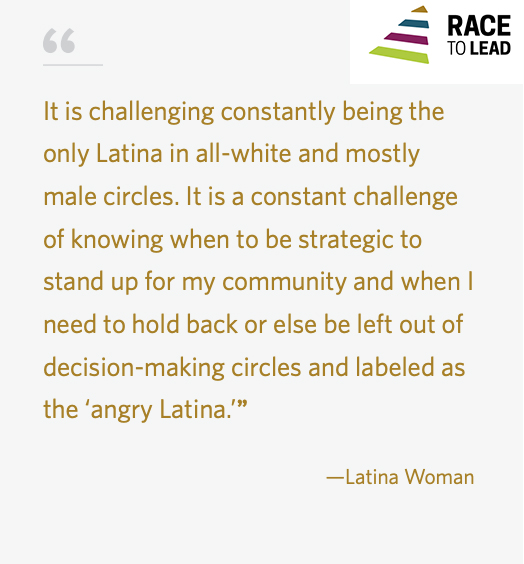

There’s a real lack of Latine leadership in Executive Director and Director-level roles; also on Boards of Trustees and Boards of Directors. There’s a real lack of representation, and this is something I’m particularly passionate about as person who served on many nonprofit boards, as someone who has had leadership positions in the nonprofit sector, that I know what it is like to feel isolated and tokenized as a transgender, disabled Latina queer person.

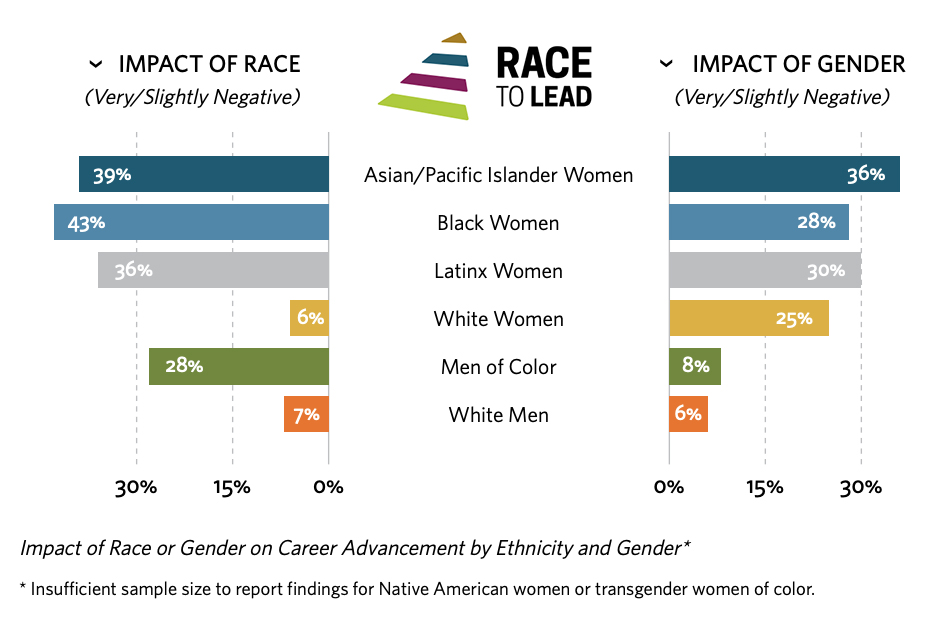

So I very much feel like there is a leadership gap, and there’s a great 2019 report called “Race to Lead” which I highly recommend. It surveyed 5,261 people in the nonprofit sector of all races about discrimination and the impact of racial bias on career advancement in the nonprofit sector.

We often think that we’re better than being racist in the nonprofit sector, but that’s patently false. As the report stated:

There is a “white advantage” in the nonprofit sector…structure and power operate specifically in the context of nonprofit organizations [to] steadily reproduc[e] concrete and experiential benefits for white people despite a stated agreement in the sector on the problems of racial inequity and the need to change those conditions.

Race To Lead Revisited, 2019

A lot of nonprofits founded by white Executive Directors and who traditionally and historically had majority white boards of directors, have real problems with not only attracting people of color into leadership roles, but supporting those Black, Indigenous & People of Color, including Latine folks.

The lack of representation of Latines in leadership that may translate into there not being attention to our specific needs, which I’ve outlined in this video about health care access, language access, understanding specifics of Latine culture, and how that impacts our autistic-ness, disability, gender, sexuality. The feeling of tokenization, as I mentioned, is really only one you can solve by putting the majority of the leadership of your organization being BIPoC, putting people in leadership roles. The more people of color on your boards and in leadership roles, the more people of color are going to be attracted to work for your organization and feel supported there.

And again, link below the Race to Lead report has great data on how to support People of Color to move up in leadership roles. They have specific breakdowns for Latines, for Latina women, for trans folks and how race impacts their leadership in the nonprofit sector.

Philanthropic organizations and other nonprofit funders and donors should really be looking to fund organizations that are led by by BIPoC folks. And I do think there should be pressure put on organizations that are historically white that still have a lot of white people driving their policy agendas to demand that they serve the communities.

So if you’re one of the people who feels marginalized, tokenized or left out of the autistic and Neurodiversity and Disability Movements, I encourage you to keep raising your voice because it’s important that we see ourselves represented.

Please Support my work and Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network

Even if you’re reading this rather than watching the video, I would appreciate it if you took a moment to subscribe to my channel on YouTube to get more content like this. You can also support my videos and writing on Patreon at Patreon.com/KayleyWhalen.

Thank you for reading, I hope you’ll check out more content on the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network blog, and consider supporting them as well.

by Kayley Margarite Whalen, Communications and Digital Strategy Consultant for the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network.