Day of the Dead in Guatemala and Mexico: Honoring Our Ancestors

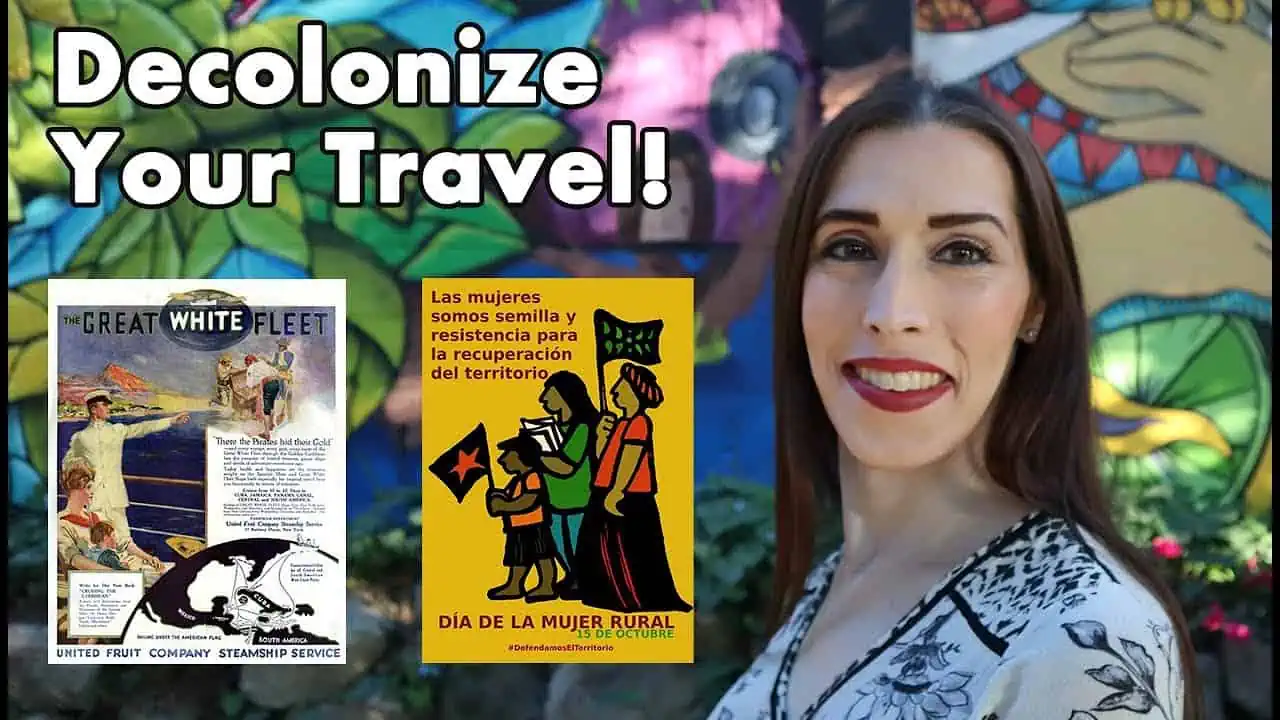

Hi, I’m Kayley Whalen, a Guatemalan-American trans and disabilities scholar, activist, and communications consultant for the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network. I’m here to talk about Día de [los] Muertos, or “Day of the Dead” in Guatemala, and how the tradition is different from Day of the Dead in Mexico. Day of the Dead is celebrated on November 1, aka All Saints Day in the Catholic calendar, and sometimes also on November 2, aka All Souls Day. And in both Mexico and Guatemala, it is a time to celebrate dead loved ones and ancestors. It’s a day when many believe the barrier between the spirit world and the mortal world becomes so thin you may be able to contact your dead family and loved ones, and even have them visit you here. This post, which is re-posted from my blog TransWorldView, is based on a video I recorded one year ago. I recommend you also check out the video!

But how do each of these traditions in the two countries differ from each other? And what do the giant kites, or Barriletes Gigantes, you see pictured here have to do with it all?

First I’ll talk about the famous Guatemalan giant kite festivals, or Barriletes Gigantes, which take place in the largely Indigenous [Maya] towns of Sumpango and Santiago Sacatepéquez on November 1. Combined, both of the large festivals draw over 100,000 people each year. Then I’ll talk about traditional Day of the Dead foods, including Guatemala’s famous salad, the Fiambre. I’ll touch on ways Guatemalans honor loved ones in cemeteries and on altars known as ofrendas, which have many similarities to Mexican ofrendas with some differences, which I’ll explain. After that, I’ll talk about sugar skulls (calaveras) and painted skull faces. I’ll also touch on some regional Guatemalan traditions, specifically the horse racing that’s held in the Mam Maya traditional lands of Todos Santos (which translates to “All Saints,” not to be confused with All Saints day). It’s a lot to cover so I hope you’ll stay with me.

Traveling to Guatemala

In the fall of 2021, I traveled to Guatemala to learn more about my Guatemalan heritage. That included being there to observe Day of the Dead by visiting my grandparents grave in Huehuetenango, Guatemala. Many of the photos you’ll see were shot then. Since then, I’ve bought additional footage from the Guatemalan kite festivals to add to the video/blog, and conducted additional research. I even made my own home ofrenda in 2022 and plan to make one in 2023.

Because of COVID, there wasn’t the big traditional party in the Huehuetenango cemetery in 2021 that there would be. The cemeteries were closed on All Souls Day and All Saints Day for very good safety reasons. Missing being part of those celebrations, which I have wanted to be part of for years, was difficult. But I did come to their grave at a quiet time shortly after Day of the Dead, where I could see other ofrendas and offerings.

Origins of Day of the Dead

But first, let’s talk a bit about the origins of Day of the Dead, and why it’s so important. Here in Guatemala, Day of the Dead has a rich history going back to Maya traditions celebrating death and the spirits after death that can come back to visit the material world. This may have looked different from Day of the Dead today, but certainly influenced it. And during/after Spanish colonization, many peoples of Guatemala carried on honoring the dead in ways that blended with the Catholic traditions of All Saints Day and All Souls Day.

Like in the old traditions, this time of the year we honor those who’ve died and celebrate their memories, rather than mourn. That way, for one day a year, they can come back and we can dance and celebrate with them.

I want to state now that Day of the Dead is not solely an Indigenous holiday, nor do I identify as Indigenous. While it is clear that Day of the Dead has some Maya roots (and Mexica roots in Mexico), at this point, it is a blend of Catholic, Spanish, and Indigenous traditions.

“Neurodivergent Narwhals” image Ed Wiley Autism Acceptance Lending Library

I was raised without much knowledge of Guatemalan Day of the Dead. This was because of the immigrant experiences of my Guatemalan grandmother Yolanda Estevez-Saras and my mother Susan Saras. Because of anti-immigrant, anti-Latine bias, and because they did not have other family in the United States, they did not typically openly celebrate their heritage or participate in large family gatherings. My grandmother also moved back to Guatemala before I was born, and I only saw her a few times in my life. But I WAS raised with a sense of Catholic traditions, which was one of my few connections to my Latin roots (even if I no longer identify as Catholic).

Guatemalan Day of the Dead Giant Kite Festivals

Kites, like I mentioned, including the giant kites (Barriletes Gigantes), are very important to Guatemalan traditions. It goes back to Maya beliefs that kites could help the people reach their ancestors, that the kite could be a line up to the spirit world, directing the spirits home for Day of the Dead. The kites are in octagonal shapes, representing the sun, with the fringes representing the corona of the sun. The four straight sides represent the sacredness of the four cardinal directions. What we’d call north, south, east, and west. The diagonal sides of the kites can ward off bad spirits.

This kite tradition later got blended with Catholic All Saints Day and is celebrated on November 1 for that reason.

Sometimes little kids also fly octagonal kites in their local graveyards/neighborhoods as part of Day of the Dead. You can see many representations of these smaller kites all year long around Guatemala. Some octagonal kites are flown year-round just for fun though! While I didn’t get to see the giant kites, I did get to see a lot of homemade kites flying as I was riding in a bus through the mountains to get to Huehuetenango.

The two most famous towns with giant kites are Sumpango and Santiago Sacatepéquez: They both have large Maya indigenous populations, and they go OVER the top with the kite tradition. They make massive kites that can be up to two stories tall, and they’re beautifully ornately painted. Many are far too heavy to fly, but are still raised up vertically to reach to the heavens. Those kites that can fly may take a team of ten to twenty people to launch into the air.

Many of the kites also carry messages and have important images painted on them. In the older traditions, the messages on the kites were intended to communicate with the spirits of the dead. But over time, many of the messages on the kites have taken on political and/or secular themes too. This includes themes around injustices faced by the Indigenous and working-class populations of Guatemala under colonization, imperialism, and right-wing Guatemalan governments, including the legacy of U.S. Interventions in Guatemala. I have an entirely separate video about that history, which I hope you’ll check out.

Image: © 2021 Kayley Whalen. All rights reserved.

Kites might also carry messages about women’s rights and the rights of other minorities, messages about cultural resistance and survival, images of dead loved ones, and celebrations of hope for the future.

The Guatemalan government has officially designated the Festival of Barriletes Gigantes as part of Guatemala’s national heritage, which will help protect these kite festivals for the future. This is a hard-fought victory for the Indigenous peoples of Guatemalan.

As I mentioned, cemeteries were closed on Day of the Dead 2021. Likewise, the kite festival that year was closed except for people raising/flying the kites, and was otherwise televised. So while I loved seeing the video of the kites that year, I plan to come back one year when it will be possible to see it in person.

Traditional Guatemalan Day of the Dead Foods:

Probably the second most famous Guatemalan Day of the Dead tradition is the Fiambre, a massive salad really only eaten this time of year. It’s typically made to feed an entire extended family who might be celebrating together, perhaps to be eaten in a cemetery. As such, it’s MASSIVE, piled high with dozens of ingredients to please everybody.

People pickle vegetables ahead of time, which are a major component of the dish, in addition to adding cold-cut meats, cheeses, and other vegetables. Often you’ll see a radish carved like a flower in the middle. My friend Ann Fratti, who helped me with the script and research in this video/blog, celebrates Day of the Dead with a vegan Fiambre dish, so that is possible. Different regions or families have their own recipes for Fiambre and one you might see is the Fiambre Rojo, or Red Fiambre, which is made with beets.

For those with a sweet tooth, another traditional Guatemalan Day of the Dead tradition is the Dulce de Ayote, a candied winter squash dish. Some of the ingredients include cinnamon sticks, a mix of cloves and allspice, as well as a hardened brown sugar known as piloncillo, aka panela.

Finally, there’s Pan de Muerto, or “Bread of the Dead,” which is very common in both Mexico and Guatemala. In Mexican traditions, this is one of the major offerings of food you might leave for the dead spirits to eat when they visit you on Day of the Dead, in addition to other dishes they may have enjoyed in life. Leaving food offerings is less common in Guatemala, but the bread is still popularly enjoyed on Day of the Dead by people. The Guatemalan version is very similar to the Mexican Pan de Muerto, with some regional variations.

The place you leave offerings for the dead in Guatemala is typically at the cemetery, especially flowers, although you may also have a home altar or ofrenda, which I’ll talk more about.

Altars (Ofrendas) and Flowers of the Dead

This altar, “ofrenda,” you can see here in my home for Day of the Dead 2022 is dedicated to my grandparents. The orange flowers, especially the marigolds known as Flowers of the Dead, “Flores de Muerto,” are very traditionally Guatemalan. I did leave food offerings to my grandparents, things they enjoyed in life, including tortillas and cooking plantains. I also left Pan de Muerto and the pumpkin I’ll be making into Dulce de Ayote. But you might also notice the sugar skull vase (it came with the flowers) which again is more traditionally Mexican. I’ll return to sugar skulls later.

But first let’s talk about Flores de Muertos, or Flowers of the Dead. These are special orange marigolds, aka Mexican marigolds, although they also grow in Guatemala! In Guatemala, if you had a loved one die in the last year, you might leave a bouquet of Flores de Muertos outside your window. This lets your local community know that you lost a dear loved one in the last year. And this means people will come around to comfort you and honor your loved one’s memory with you, which I think is a pretty great tradition.

You’ll also generally see these flowers in nearly every bouquet left at graveyard ofrendas, possibly with other flowers.

Regional Traditions (Todos Santos Horse Race)

As I mentioned, there are also some regionally specific traditions. Right near my grandparents grave in Huehuetenango is the province of Todos Santos. It’s the ancestral home of the Mam Maya people, who to this day remain the primary inhabitants. Todos Santos is famous for their horse races held during Día de Muertos, which have a bit of a dark history.

Legend goes that these horse races started as a protest to Spanish oppression and how the Spanish saw indigenous Maya people as culturally inferior. According to one story, some Mam Maya overheard Spaniards talking at a bar about how Maya people didn’t know how to ride horses. Well, the Maya men who overheard this, after a few drinks at a bar, stole some Spanish horses in protest and raced off with them. This origin explains or, perhaps justifies, why these horse races are typically performed along with heavy drinking, and also why the people riding the horses wear the traditional clothes based on the costumes that the Spanish colonizers forced men to wear to mark them as Mam Maya.

Because of the drinking, there’s been some criticism around the safety and ethics of these horse races, and the Guatemalan government officially banned liquor sales around that time. But in continued defiance, the chaotic party atmosphere of the races and some drinking continues.

While I did visit Todos Santos a few months before Day of the Dead with a local Maya guide, I was not there for Day of the Dead itself. I would give travelers the advice that the region is not set up for heavy tourism and the local peoples are fighting hard to preserve their culture.

So I would think hard about going to Todos Santos for Day of the Dead, and perhaps recommend going to a kite festival such as in Sumpango or Santiago Sacatepéquez instead. Both have more tourist infrastructure. But if you do wish to go to Todos Santos, please educate yourself about the local Mam Maya people first and be respectful. One rule is never take photos/videos without explicit permission, especially because of local customs and taboos around photography.

Skulls and Skull Face Paint

Regarding sugar skulls, “calaveras,” while they are one of the most recognizable aspects of the Mexican tradition, they do not play a major role in most Guatemalan traditions. That said, Guatemalan towns which are closer to the Mexican border tend to have a mixture of Mexican and Guatemalen beliefs and practices. This includes Huehuetenango. While visiting shops near my grandparents grave, I did see sugar skull decorations on sale.

Photo: © 2021 Kayley Whalen. All rights reserved.

In the small town of San José in Petén, Guatemala there’s also a tradition of La Procesión de la Calavera, the Procession of Skulls, which involves honoring the skulls of the three founding ancestors of the town who belong to the Maya Itza ethic group. It is a celebration of the town’s historic resistance to Spanish colonization and the importance of preserving traditional beliefs. So you will definitely see skulls as part of the Día de Muertos traditions specifically in this town.

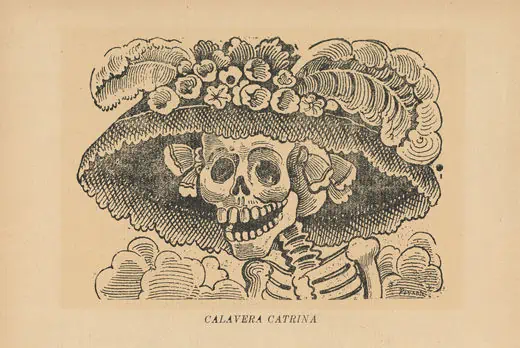

One other thing is I brought with me to Guatemala from Mexico to my grandparents’ grave was some of the traditional Mexican cut paper ornaments they display over ofrendas and at celebrations. Cut into these papers you regularly see the “Calavera Catrina” figure, whom is very famous in Mexican Day of the Dead celebrations.

Calavera Catrina started as a parody illustration of a Mexican woman with a skull face (a “calavera”) who was trying to put on airs by dressing in a Spanish colonial style including a big fancy hat with feathers. This “Calavera Catrina” woman, meant as a critique of Spanish imperialism, turned into a big part of Mexican Day of the Dead celebrations. She’s in art everywhere, and inspires many people to paint their faces as skulls and wear fancy hats. I explored the Calavera Catrina in Mexico in another video about the goth subculture of Mexico and how it blends with Day of the Dead, so do check that out.

Image: © 2021 Kayley Whalen. All rights reserved.

There is sometimes controversy over whether it is appropriate for people to paint their faces like Calavera Catrina or candy skulls for Day of the Dead. It’s a question even I’ve grappled with since even though I am Guatemalan, I’m not Mexican. I think it’s also complicated by the way that there are often “pan-Latine” celebrations in the US practiced by a blend of various peoples and traditions with roots in Latin America. I particularly enjoy how the Calavera Catrina figure originated as a political cartoon in protest against the forces of colonization. So I feel if you’re going to incorporate Calavera Catrina costumes and/or painted sugar skull faces into your traditions, it’s important to do so in a way that resists colonialism rather than reinforcing it through co-opting other people’s cultures. No, I’m not going to discuss Disney’s movie Coco here, that would be it’s own essay. But if you’re Mexican or Guatemalan or Latine and have other thoughts about the politics of Catrina and painted-skull faces for Día de Muertos, I’d love to hear from you.

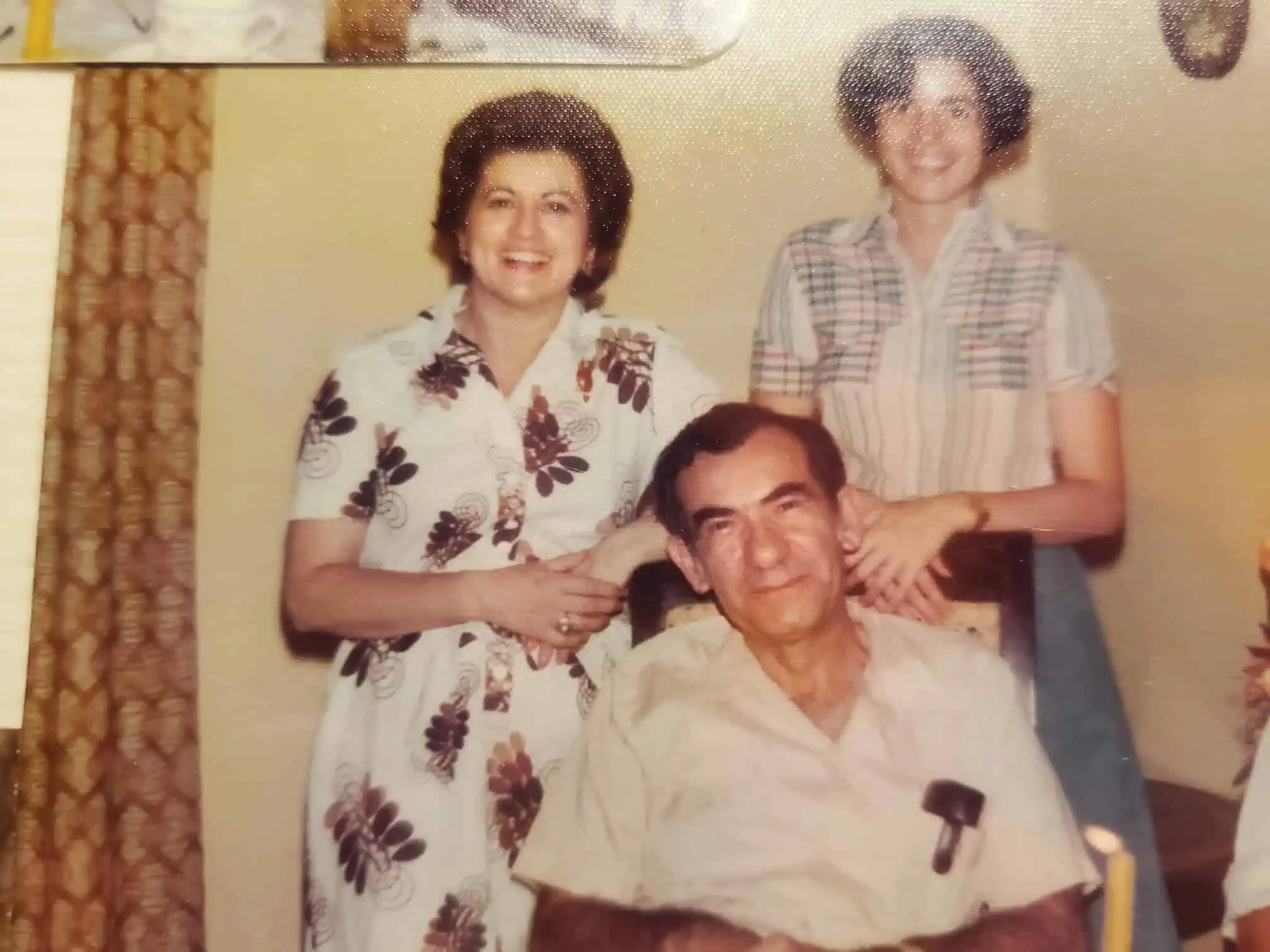

My family’s immigrant experience

Earlier I alluded to not having much connection to my Latine roots. So I wanted to talk about some hard truths about being from an immigrant family, and about the Latine experience in the United States. There’s this American pressure to assimilate to dominant white culture, which my grandmother and grandfather felt strongly as people from Guatemala and Puerto Rico who moved to New York City as young adults. They also raised my mother in Queens in a neighborhood with few other Latine people.

Photo: © 2021 Kayley Whalen. All rights reserved.

This pressure to assimilate often leads to our beliefs and traditions not being passed down. So I’ve asked my mom a few times what she knows about Day of the Dead in Guatemala, and she just didn’t really have a strong knowledge about it and. She did remember a bit about the Fiambre salad, and she did remember a bit about kites that her parents told her about. I was raised Catholic, but Day of the Dead was not part of how I celebrated.

I was taught death was something scary, which I internalized. Death, how I was raised in dominant US (white) culture, was all about mourning, about sadness. Day of the Dead is unique from many other traditions around death because of the idea that you can still celebrate with your ancestors, their spirits, after they die, which makes death beautiful, not scary. And that’s why Day of the Dead exists. It’s a day of festivities. What’s so beautiful about Day of the Dead in both Guatemala and Mexico is that it is a celebration of life. It is a celebration of children and family and ancestors all being together for one time of year and, instead of being afraid of death, knowing that we can live life joyously while still honoring them. Knowing that for one day a year, they can be with us and we can be with them.

If you got something from this blog post, please consider supporting me on Patreon. Patreon.com/KayleyWhalen and supporting Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network.

Also, thank you to Guatemalan LGBTQ activist Ann Fratti for helping with research on this post. And thank you for being hear to learn about Day of the Dead. ¡Feliz Día de los Muertos!

This blog originally appeared on Kayley Whalen’s blog, TransWorldView.